Strands of work on stakeholder engagement and behaviour change have been woven together in a couple of different pieces of work I’ve been doing with public sector clients recently. I’ve ended up developing some new frameworks and adapting some existing ones to help people clarify their aims and plan their campaigns. If you want to influence someone to change their behaviour, there are models and approaches which can help. For example, the six sources of influence help you identify the right messages and pay attention to the surrounding context which supports and enables – or discourages and gets in the way of – the desired behaviour.

When you are working for a public body (the NHS, a Government department) and you are trying to influence the behaviour of people who you have at best a distant relationship with (mothers, or people who buys cars) then you will go through a multi-stage process:

Should we be trying to encourage this behaviour change, which we see as desirable?

If yes, what role(s) should we be playing (legislator, educator, convenor, funder etc)?

If yes, what are the most effective ways of influencing the behaviour?

Should we encourage this behaviour change?

Given current discussions about social engineering, this question is important. It might seem entirely obvious and uncontroversial to us that wanting to promote energy efficiency that more efficient light bulbs should be promoted. So obvious that we don’t stop to consider possible unintended consequences or misunderstandings.

So an important early stage is to engage stakeholders in helping to inform the decision about whether to encourage a particular behaviour change at all. For this, classic stakeholder identification and mapping techniques (e.g. see figure 1 in this paper from WWF) will help ensure that you hear from more than the usual suspects.

Stakeholders can share perspectives about the policy goals, identify which behaviours might help to achieve them, and whether action to encourage those behaviours is a good idea.

What role should we be playing?

Some public bodies draft new legislation and regulations, others deliver services. Some enforce regulations and others provide advice and public education. Some bring other organisations together, convening conversations and partnerships. Others commission and fund research. There are lots of roles that public sector organisations could play in a given situation. Which role or roles make the most sense, in meeting the policy aim in question?

Listening to the views of stakeholders in relation to that question is enormously helpful. And those stakeholders may be professionals who work in that field of expertise - but removed from the coal face - or they may be practitioners on the ground whose direct experience can bring a dose of reality to the conversations.

A great example of this is the Low Carbon Communities Challenge, launched on Monday 8th February. It will (amongst other things) draw on the experiences and insights of 22 communities which are being funded to install energy efficiency kit and renewable energy equipment en masse in their areas. They’ll also be encouraging people to adopt low-carbon behaviours. Each community will be doing something different, guided by its particular circumstances and enthusiasms. Excitingly, each community will also be asked to identify the barriers to and enablers of progress, in particular what government could do differently to make this kind of low-carbon push as successful as possible across England, Wales and Northern Ireland. I'm delighted to be a facilitator on this project.

What are the best ways of influencing this behaviour?

A cool analysis of the system of players and pressures which lead to the current patterns of behaviour is a good starting point, and involving a team (including some stakeholders) will help ensure that the picture built up is rich and complete.

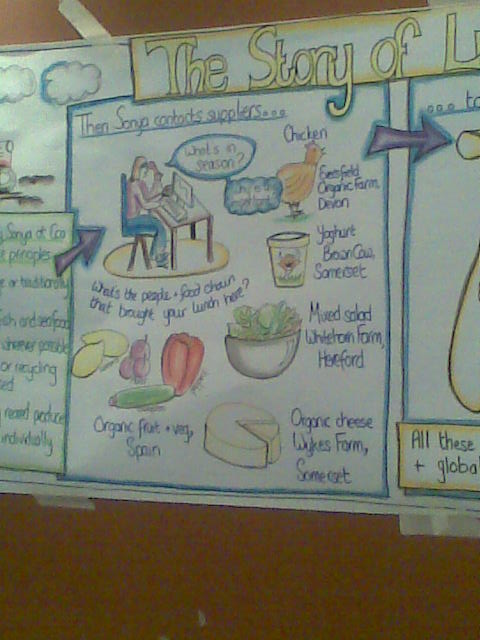

In a workshop a few weeks ago, we used the classic ‘pestle’ headings to brainstorm the pressures and players which influence a particular behaviour which my client is interested in changing. Let’s say that the behaviour is keeping one’s car well-maintained, so that it runs as fuel-efficiently as possible. Specific behaviours include keeping the tyre pressure optimum, and removing the roof box when it’s not needed.

In the workshop, people identified players and pressures and wrote them on post-its, sticking them up under the headings of Political, Economic, Social, Technical, Legislative, Environmental and Other. The headings and team-work both help to ensure that no aspect of the system is forgotten.

Once that was done, we stood back and looked at the results, and pictures were taken on a camera phone. Then I invited people to bring the post-its to a big blank sheet of paper, and to begin mapping the relationships between the players and pressures, starting with “the most interesting” element of the system. [The idea of asking for ‘the most interesting’ came from a book about coaching which I’ve been reading.]

One post-it was brought to the empty map, and was soon followed by others. Lines of connection were drawn, and amid the chaos some patterns emerged. Most importantly, the team realised that these behaviours were more like DIY and home maintenance than like ‘eco’ behaviours, so when targeting different audiences they should seek our market research which segments people according to things which are relevant to that kind of behaviour, rather than segmentations which have been developed with an environmental purpose in mind.

Mapping stakeholders for behaviour change

This brought us smoothly to looking at which stakeholders to engage as a priority, to add muscle to the campaign to influence people to adopt (or reinforce) the desired behaviours.

Many of these stakeholders were ‘players’ identified in the earlier exercise. Some were organisations and people who the team thought of as the system was being mapped.

As a variation on classic impact /influence matrix, and building on the ‘who can help me’ matrix which I use with organisational SD change champions, is this diagram.

Brainstormed onto post-its, stakeholders are then mapped according to the team’s view about their influence and attitude.

You then overlay the coloured ‘zones’ onto the matrix, and these are linked to typologies of engagement like the ladder of engagement.

The people and organisations which are the highest priority to engage with, are those who are highly influential and have the strongest opinions (for and against) the desired behaviour change. In-depth engagement which involves them directly in designing and implementing the behaviour campaign will be important.

Those in the ‘enhanced’ zones need to be involved and their opinions and information sought.

Those in the ‘standard’ zone can be engaged with a lighter touch – perhaps limited to informing them about the campaign and the desired behaviour.

The workshops helped these clients to identify new stakeholders, reprioritise them, and consider more strategically who to engage and to what purpose.