My client drove me to the station from our rather remote venue this afternoon. She said:

"Do you think about a workshop after it's over, or..."

I mentally completed her sentence as "or don't you manage to?" After a small pause, she finished

"...or are you able to let it go?".

I was reminded of the usefulness of not assuming you know what someone else is going to say.

And I realised I'd filled the pause with my own self-criticism: because I'm intellectually committed to action/reflection, and thinking about a workshop after it's over is a powerful reflection stage.

But sometimes I'm just too tired to concentrate on reflecting 'properly'. And I might beat myself up about all the scintilating learning I'm missing by not journalling or even blogging as much as I might.

Instead, my mind wanders or I retreat into the self-indulgence of a journey home where I can read the paper, mess up the Kakuro or stare out of the window.

But this particular journey home has been longer than expected, and I've got my second wind. So I will 'reflect properly', drawing on what we talked about and thought about on the way to the station.

You're working too hard

One of the things my assessors said after my CPF earlier this year was that I was working too hard. The group should be doing the work, I need to get out of their way. Perhaps I can take the same advice about reflection on my facilitation: let my mind do the work and get out of its way.

Wandering mind

The drive to the station was quite long, so I did let my mind wander, sparked by my client's question. We had one of those leisurely conversations which are interspersed with gentle silences. And our conversation touched on spaces, client comfort and workshop plans.

Owning the space

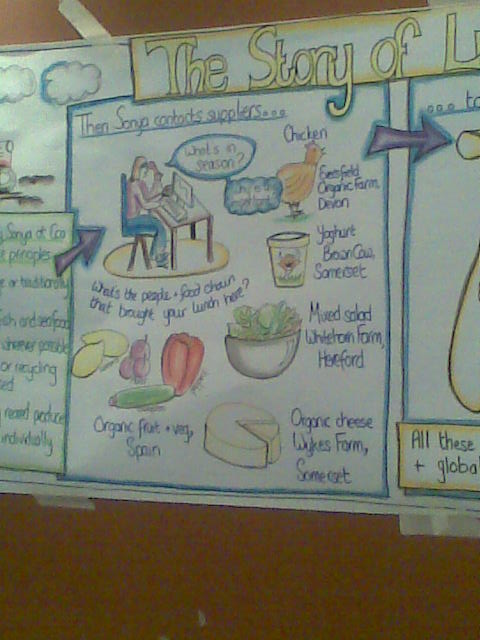

My mind wandered to what we had done to own the space. This workshop was the third in a series of three and all the venues we used had their challenges. Two of the three lacked good smooth walls to stick flips on and write on. Today's was crowded and we had to prop up boards on tables and stacked chairs to be able to see the flips.

In every venue, we quickly assessed the room, decided which furniture to move around or move out of the room altogether, and worked out where we would display the flips we needed for various metaplanning-type exercises and for participants to be able to see the running record.

Over the years, I have had to learn about the importance of layout, gain the confidence to take responsibility for making spaces as good as they can be for the conversation we want to have, pick up some tips and tricks for improvising the space and equipment needed, and get more decisive about making changes rapidly. That experience has paid off today.

Over-identifying with the client: whose comfort?

I have been more conscious recently of my own tendency to over-identify with my client, when facilitating stakeholder workshops. I feel uncomfortable when I think the client team may be feeling uncomfortable. I feel relieved when I think they may be feeling relieved.

I'm confident that this is not having a significant effect on my facilitation, but I'm conscious that this is a danger and that I need to check my inner motivation when choosing to intervene (or not) in situations where I believe that I know what my client would like to hear. Holding the space in periods of discomfort, doubt, uncertainty, conflict, anger, disappointment - this is one of the special gifts which a facilitator can bring to a group, and I'd like to strengthen my ability to do this with ease, without being overly concerned about the client's level of comfort.

As it happens, today I was impressed with how well the client team responded to some of the things stakeholders said, which were probably hard for them to hear. Defensiveness was mostly absent. When the team thanked people for sharing their experiences, perspectives, frustrations and aspirations, I think they meant it.

If I had, even unconsciously, sheilded the client from this difficult conversation, then I might have avoided some temporary discomfort (largely my own?) but I would have prevented some important truth-telling and mutual understanding from emerging. And the elephants in the room would have remained hidden in plain view.

Let go of the plan

In two of the three workshops, we radically redesigned the agenda part way through the day. A wise facilitator once said to me that any fool can design a workshop, it's being able to redesign on the hoof that is the mark of greatness. I wouldn't claim to greatness, but my redesigns were good calls!

Today's was helped enormously by the intervention during lunch of a process-savvy participant who observed that what the organising team wanted to talk about was not what the participants wanted to talk about. We negotiated a 'deal' to split the afternoon's work so that some time was spent on the more pedestrian but urgent client concerns (and the group threw themselves into this) but a larger chunk of time was allocated to some open space. This was agreed by the rest of the group.

As my client and I discussed this on the way to the station, I was reminded of some insights about planning.

- At this AMED event last Friday, we talked in passing about Eisenhower's claim that "plans are useless but planning is indispensible."

- A few days before, at an ODiN workshop organised by Chris Rodgers, someone talked about their frustration at hearing people use 'opportunistic' as a way of disparaging those charities which apply for funding without a nailed down strategic plan.

- And my reading of this new sustainability leadership book containing experiences written through an action research lens has helped me understand how intention, values and an understanding of what you feel drawn to do can be coupled with being alert to opportunity resulting in emergent strategy. (There's an explanation of emergent strategy here, but you may know of a better one - stick it in the comments.)

I think there's a parallel here with workshop (re)design:

- some values underpinning your work as a facilitator,

- some shared aims (intentions) agreed with participants,

- an understanding of the expertise and resources (e.g. time, space, numbers of different kinds of people, access to information) available for the conversation.

- being alert to 'what's trying to happen here' and getting out of its way.

If you have those things - as a result of doing some planning (having a conversation about planning) - then a strategy is able to emerge if you get out of its way.

Update: This today (1st October 2011) from Dave Pollard would call this resilience planning, rather than strategic planning. An interesting post.

The conversation goes where it goes - who knows what might have happened if...

What I didn't follow up on was the confession which may have been present in my client's question: does she find herself unable to let go after a workshop, dwelling on what might have been in a way which doesn't help her learn but perhaps keeps her in that unconfident phase of believing that she hasn't done well enough?

I don't know. That conversation may have been equally rich. The coach in me would have gone down that route, but the coach in me was taking some time out.

But by not trying too hard, and offering my own meandering observations, I reflected properly on what I'd learnt from the day.